When I was around 10, an age notable for its insurmountable mountain of childhood ambitions, I came to the conclusion that the best thing I could ever be was fast.

At the time, the revolving doors of my dreams spun largely around beating the fastest boy in my grade in the end-of-the-year race on field day. Clutching this dream like a rosary, each step in my day and mark off the calendar a prayer bead to trace on my way to the victorious enlightenment. Reaching through being christened the fastest, penultimate ire of 5th-grade boys and king of the girls, I became a devout patron of the art of speed. I infused this divinity into my veins in the hope of sweating it back out into everything I did, training in the temple of my mind to be ready to reach my destiny.

On race day, I was to slink through the underbrush of turf, unseen as a jaguar (a jaguar wearing a bright green jersey) stalking its prey, and find myself at the finish line with an invisible, almost preternatural speed. At the moment my existence boiled down to, I was to claim what was mine. I was certainly not to pull my hamstring.

Which is, of course, what I did. I came second in the race. The finish line, instead of welcoming me into the radiant warmth of my ascension to God of the 5th grade, acted as a shining guillotine poised to take me down to the depths of my shame.

I never ran again.

Recently, while wearing pacing circles on the school carpet, a dear friend told me that the word amateur, an evident novice at their particular craft, stemmed from the Latin word “amator”, directly translating to “lover”.

The entire conversation brought me walking, now much too out of practice to run, back into the tender, self-made church on the farthest hill cresting my then elementary school, where the race took place. Traversing the winding corridors of the hopes of a little girl, perhaps embroiled in delusion but leaking passion, I was grief-stricken. How could I have allowed one loss to drive me from the ceilings of my love?

And, in entirety, it brought me to this conclusion: the, specifically American, desire for absolute and notable success has driven us from the beauty in pleasure.

As we tumble further into the frightening unknown of the 21st century, it seems that the population has contracted a disease carried by the horse-blinders of capitalism. Blocking out the rest of the universe, we now only have eyes for the vague, imperceptible mistress of accomplishment.

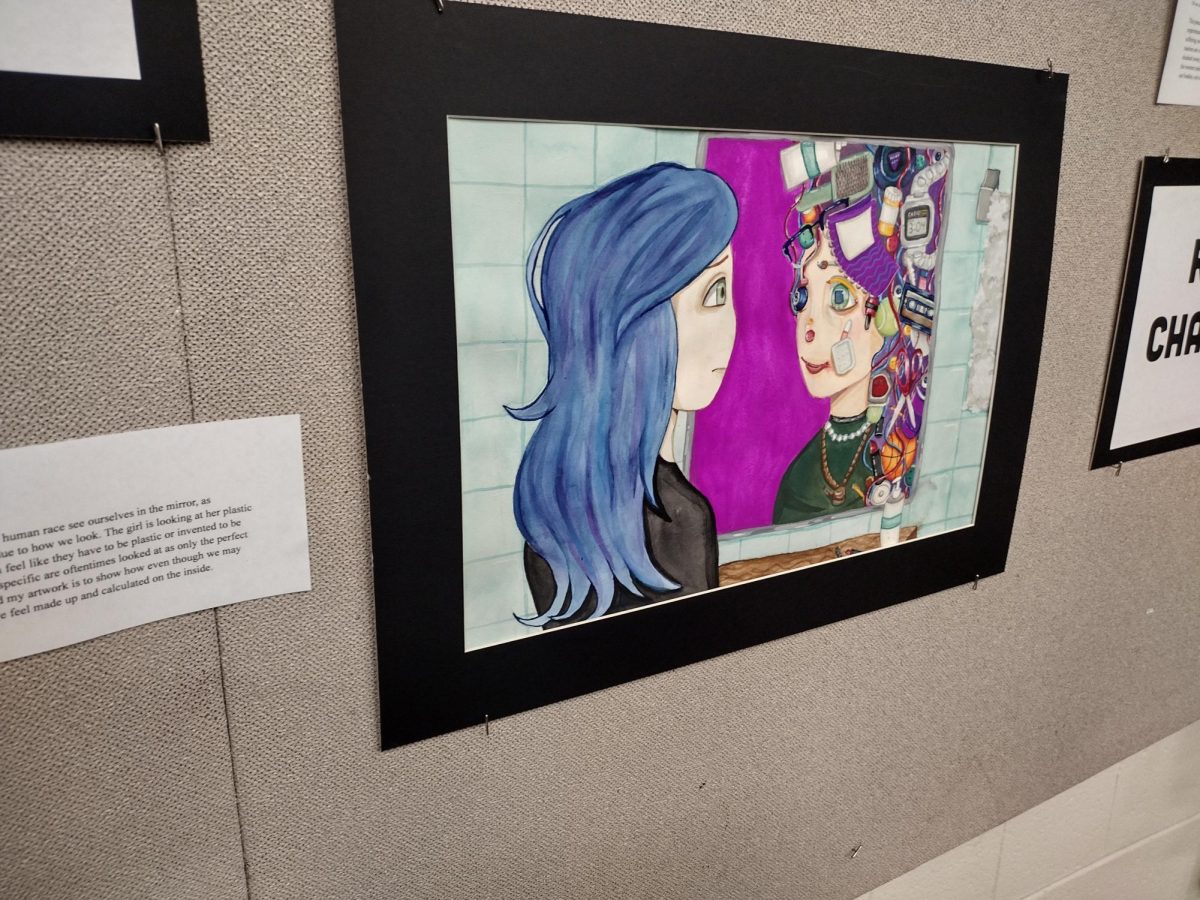

Instead of leaping fearlessly into the arms of the breathing, living world overflowing with creative potential, we cower in the fortresses of our cubicles and clutch at whatever singular true “talent” we feel we have been allotted by some unknown benefactor like a shield. The people have come to fear the inherent grandiose achievement and success in taking up the mantle of amateur. The people have come to fear the intrinsic art of doing what you love.

But this is by no mass hallucinatory mistake, especially not in a country most revered for its herculean standing of “advancement” on the world stage. America’s system of capitalistic, profit-driven progress would be halted, perhaps even entirely struck down, if everyone simply did what they loved. We would cease our attempts to be “the best”, to be considered “useful”, and would, instead of mindlessly producing for the sake of quick “advancement” and validation, herald in an era of passion.

If the world woke from a collective, consumerist reverie and looked up from the altar of their piety to the sole pursuit of an undefinable, often unachievable, preconceived “talent” to gaze at the Gothic rafters of the church of the world in which they find themselves, they would tumble up the rabbit-hole into the sky.

They would see the crushed shell paint and scientific glory woven into the Renaissance and its bounds into modern advancement. Forensic evidence of the serene, cherubic world of Botticelli and the grimly surrealist, aching crawl upon the cracking of sinful bones which both Dante and Bosch have taken on as rites of passage into the halls of history has become slathered all over culture.

Perhaps they would remember the naturalistic clash against society, with word wielded as weapon, of Romanticism and its intimate molding of language into decades to come. Or the bricks of sweat, tears and creation used to build Harlem into a black cultural mecca during its own 1930s Renaissance. Perhaps they would see the historic, arcane periods of beauty, not of perfection, which created much of our world.

So, even though I have left behind my worship of the wind and my holy 5th-grade fate, I still strive to gaze at the details of my temple, built to memorialize my ardent devotion to whatever I do. To bask wholeheartedly in the imperfections of my many loves and their ink-stained marks upon even the smallest, most fragile epochs of the world.

My understanding of the cure to our disease is extraordinarily simple, and something I have reiterated many times, grasp with fervor onto all things you place into the world from the heart. Recognize that love is the entity that breeds true “talent”, and you will come to understand the human progress, personal and collective, which always twirls about the beauty in the painstaking craft of all amateurs, of all lovers of the world.