As a Korean immigrant who was predominantly raised in America, I was always confined by the eyes of expectation. In my childhood and younger adolescence years, I was expected to prepare myself for the future that would supposedly “define” my career and trajectory in life. This preparation and the future circumstances that would be brought with it were narrowed down to a prestigious university or a well-paying job to please the ever-so-tiger parents of an Asian household.

I had just recently come to the conclusion that my path in school, extracurriculars and a retail job on the side was a mirror image of my parents who had worked diligently to be the only ones in their family to cross physical borders and set a new course of events for themselves- to touch the foreign land of “unknown” and make a living from it.

My childhood was filled with a roof over my head, a dependable education and comfortable living. Days consisted of riding on the neighborhood swingset and nights were reserved for family movie time.

Now, as a student in my final year of high school, I contemplate my past experiences, memories and lessons that I picked up on the way when I was the younger version of myself. These actions that led to my existence in the now all had the underlying reality of what it means to be an immigrant and a child of immigrants.

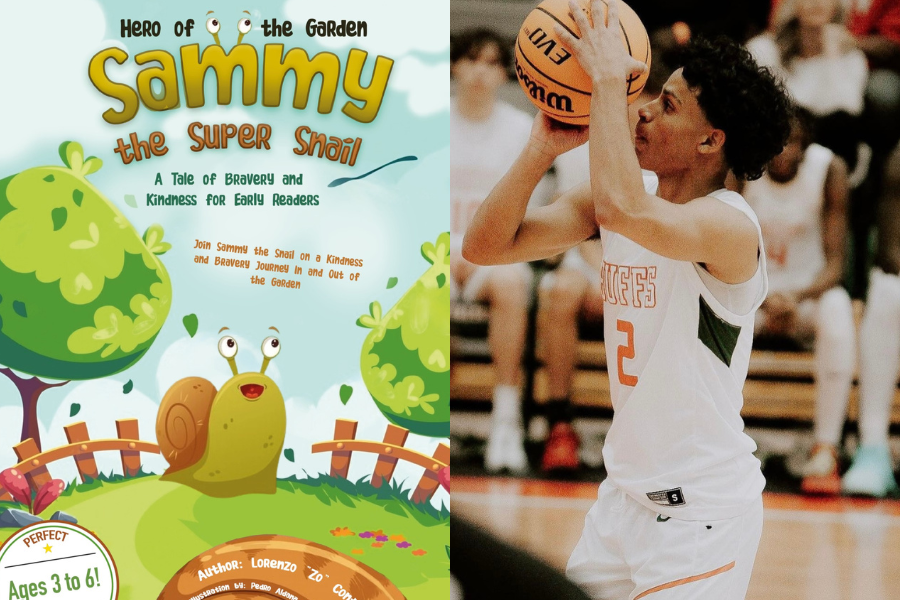

When I open the Common App tab on the internet to resume my college admissions process, I think about how all the components of an application are within my fingertips to represent my participation in clubs or leadership positions at school to fully sell myself to a university. This is what success could mean in a literal sense while I cross my fingers and hope for a letter of acceptance.

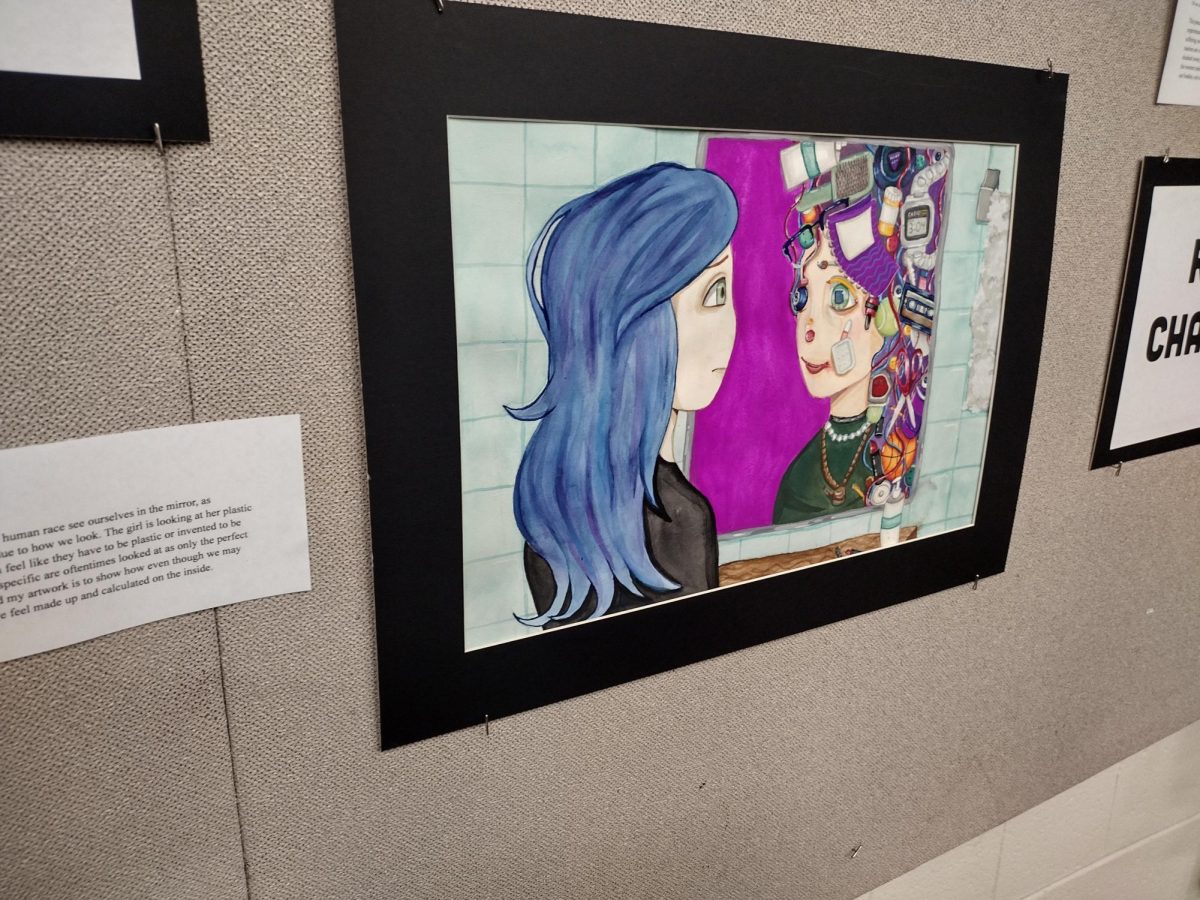

However, I can now fully comprehend what “first-generation success” could mean in the eyes of the beholder, myself, rather than the validation sought from others. As a Korean woman, daughter, immigrant and student, success looks quite different to my set of beliefs and values than it would to someone else who identifies with my culture or religion.

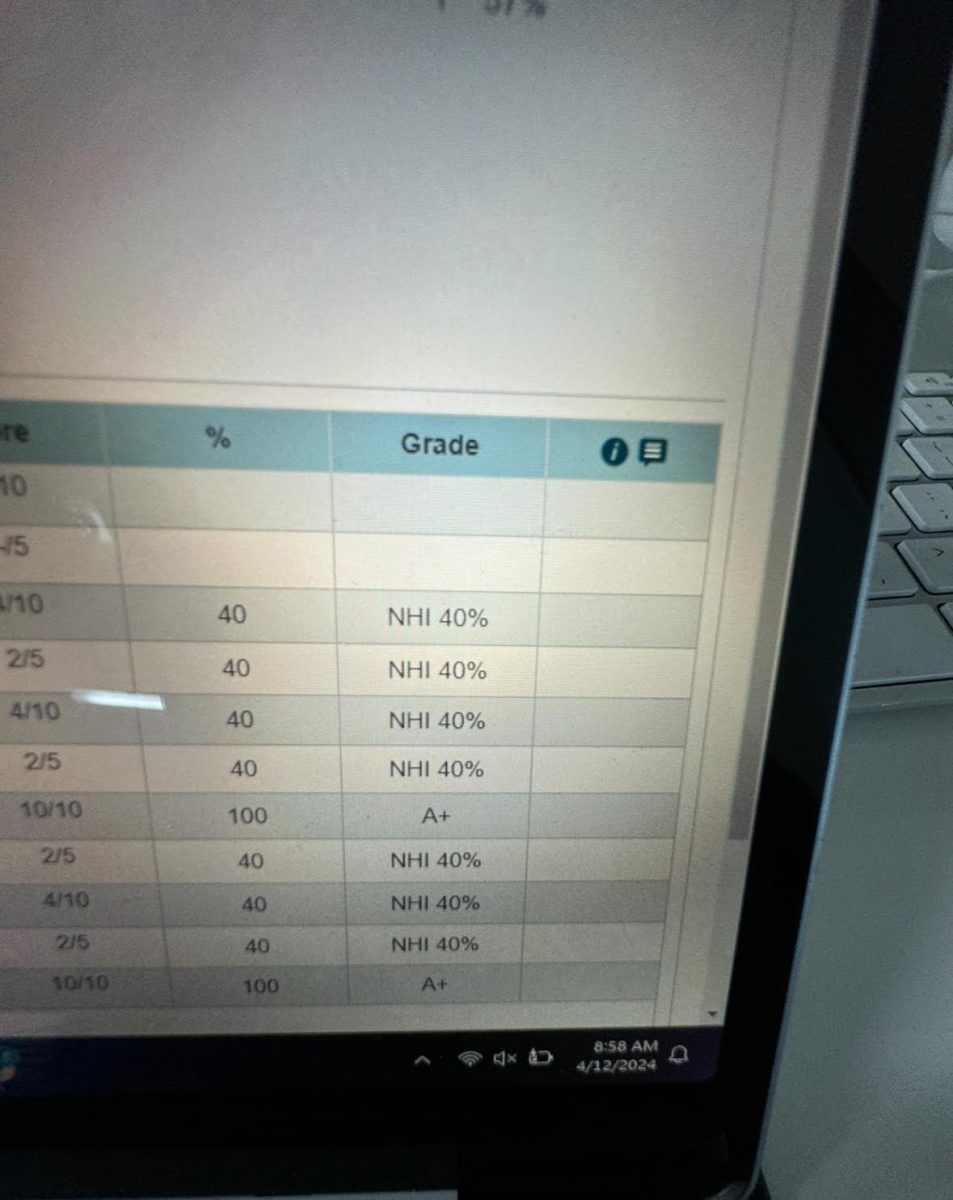

Despite the copious amount of hours spent at the library studying or completing assignments in a timely manner, my grades and academic performance defined my success to my parents or a school transcript. The Korean culture I identify with romanticizes and praises an idealistic “student” in society who prioritizes their education to be first. But now, I recognize the effort and the consistency it took in order for an outcome in the form of a letter grade or test score that doesn’t dismiss myself.

My hard work is not restricted to something so inanimate like receiving a perfect A on a final exam, but unbounded by my passion or drive that is authentic to my character and how I choose to embody the account of narratives that make up for it.

I continue to validate and express my gratitude for the position I find myself in today. Whilst being fully aware of the privilege I have and the opportunities that are given, I can say that being a first-generation student, daughter or young adult equally brings a set of new rules and guidelines unique to myself. Being first-generation means to be the first to bring a new perspective or a voice to the table- success is meant to be wherever you decide to pursue it.